There is a moment in every athlete’s life when they face trials and tribulations. For Chaz Misuraca, that moment did not come in the form of an opponent or a grueling training session, but in the slow, inevitable loss of his sight. The world of sport, once familiar, became an enigma, a puzzle that required reconfiguration. But Misuraca’s story is not one of surrender. It is one of reinvention.

If you listen to Misuraca speak, you begin to notice a pattern. He talks about obstacles the way a mathematician talks about equations: solvable, malleable, a series of questions waiting for answers. Where others might say, I can’t, Misuraca asks, How can I? It is a deceptively simple shift in mindset, but for someone navigating the world without sight, it is the foundation of his success.

Like many elite athletes, Misuraca understands struggle. But the struggle he describes is not just the physical exertion of climbing rock faces or competing in blind hockey. It is the struggle against the narratives we impose upon ourselves—the idea that disability means limitation. This is internalized ableism, which happens when people with disabilities start to believe the negative messages society sends about them. Our culture often treats disability as something “less than”, a deviation from an ideal norm and therefore a problem. These ideas are reinforced through social norms, policies, and our institutions (Campbell, 2009).

“Everything’s hard at first,” he says. “When we’re kids and we try to learn how to walk, we fall a thousand times, but we never say, ‘Walking’s not for me, it’s too hard.’”

Climbing without sight

Misuraca didn’t start out as a climber. In fact, he only picked up the sport after losing his sight, which meant he had no reference point for what climbing should be like. In many ways, that was an advantage. There was no sense of loss, no comparison to how things used to be. There was only the challenge in front of him.

Climbing blind requires a unique approach, one that relies heavily on trust and precise communication. Misuraca competes with a sighted caller, who acts as his eyes on the wall, and a belayer, who is responsible for securing his rope and safety whilst climbing. His caller provides verbal cues, describing holds, movements, and route sequences. Misuraca must translate these descriptions into precise body movements, feeling his way through the climb with heightened spatial awareness.

For a blind climber, the ability to visualize the route mentally is critical. While a sighted climber can scan a wall and adjust their approach mid-climb, Misuraca must build a mental map in real time, relying entirely on tactile feedback and his caller’s guidance. It’s a dynamic process that demands not only physical strength but also an acute sense of balance, problem-solving, and trust.

Misuraca’s schedule is a balancing act between climbing and blind hockey, two sports that complement each other more than one might expect. His climbing season runs from late May to fall, while hockey wraps up in March, making it manageable to pursue both. What’s more, the physical demands of climbing—core strength, flexibility, grip—have directly improved his performance on the ice. “My shot has gotten better because my wrists and forearms are stronger from climbing,” he explains. “A lot of the training overlaps. Both sports require agility, balance, and full-body strength.”

Perhaps the most fascinating element of Misuraca’s journey is not his own success, but his relentless pursuit of making things easier for the next generation. He sees his work not just as personal achievement, but as laying down stepping stones for others.

“The more things I figure out, the more I can teach them,” he says, referring to blind children who want to try climbing. “If I can do it, they can do it.”

Ability and disability are often thought of as absolute and as a binary – you are either disabled or not disabled. This is something disability scholars have pushed back against (Goodley, 2017; Withers, 2012). The nature of disability is fluid and changes depending on context. Attitudes, policies, structures and environments can all be disabling.

Misuraca pushes against the arbitrary borders that define what is and isn’t possible. When first asked to go backcountry skiing, he hesitated. I can’t do that, I’m blind. But then, like so many other times in his life, he reframed the question: How can I do this? Today, he skis, mountain bikes, and rock climbs, defying not just external expectations but his own preconceived limitations.

And yet, Misuraca is keenly aware that his personal determination is not the only variable in this equation. Access and opportunity play crucial roles. Funding, the physical or architectural environment, technology, communication or information are all factors in either enabling access, or in creating barriers. A licensed diesel mechanic, he left full-time work because the job was hazardous to his health. The carcinogens were worsening his sight, and the shop, while supportive, was a ticking time bomb of occupational risk. When the location moved further away, Misuraca faced a choice: spend $100 on a cab to get to work every day, live at the shop and forgo training, or walk away. He chose the latter.

Instead of chasing paychecks, he found purpose elsewhere—mentoring young blind athletes in hockey and climbing. But his work isn’t just about introducing kids to sport. It’s about showing them that they belong. He has run climbing programs for blind children, funded by nonprofits, but he recognizes that far too many kids are still left without opportunities.

“I’ve worked with eight kids,” he says. “But there are so many more who want to climb, and their parents don’t know how to help them.”

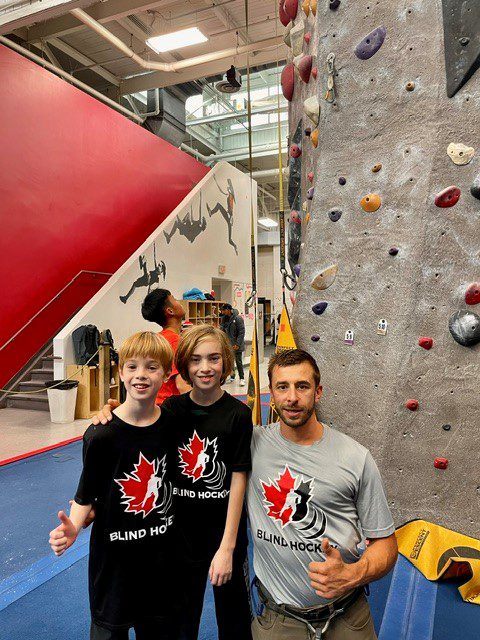

Misuraca is passionate about showing kids that losing their sight doesn’t mean losing their ability to play sports and be part of a team. He regularly participates in events that introduce blind children to rock climbing, soccer, judo, and other activities, giving them a chance to explore their potential.

“I really enjoy sharing with the kids how awesome my life got after my sight loss,” he says. “I see a lot of really sad children. It must be so hard to go through sight loss at 10 years old. I was 32 when I lost mine, and even then, I had my adult friends pushing me to stay active.”

Rewiring the narrative

Climbing, he insists, is for everyone. But the systems in place do not always reflect that belief.

“A blind person’s body still works completely fine,” he says. “But if you’re missing a leg or both legs, or you’ve had a broken back, or you’re not physically strong enough to climb under your own strength, then we use this pulley system that helps cut the weight. Someone is on the other end of the rope, and they can pull as much or as little as you need them to.”

It is a simple solution to an unnecessary problem. The real challenge is not the physical act of climbing but the perception that Para athletes require costly or time-consuming accommodations. In some cases, the simple adaptations Misuraca mentions aren’t considered as a possibility. But he doesn’t see it that way. Climbing is climbing. Sometimes you need an extra rope; sometimes you need an extra hand. The relationships in Para sport, such as between a guide and athlete are often interdependent – both parties relying on each other and contributing equally to the relationship. It’s a partnership. Bundon and Mannella (2022) highlight the relationship and partnership between visually impaired athletes and their guides and the lack of recognition and perceived value in this type of interdependent relationship.

One of the efforts to grow Para-climbing in Canada is a program called CLAP: Climb Like a Para Climber. These events, which Misuraca has participated as a volunteer, invite non-disabled climbers to experience Para-climbing firsthand. The program has set up competition formats designed to educate people on the different accommodations and adaptations in climbing, making the sport more accessible for all. Participants climb blindfolded, restricting their vision to experience what it’s like to rely solely on a caller’s guidance. Others tie up a leg or tape a hand, simulating various physical impairments. Initiatives like CLAP are helping to build partnerships and relationships between climbers of all abilities and is breaking down divides.

What makes CLAP so effective is that it forces climbers to confront the hidden challenges Para athletes face daily—not just on the wall, but in all aspects of preparation. At one event, Misuraca said a climber attempting to tie his shoes with one hand became frustrated at the simplest of tasks. And for the first time, he understood that Para athletes are navigating barriers and challenges beyond the climb itself.

Misuraca has been climbing for 6 years, though for half that time, he believed he was the only blind climber in the world. It was only by accident that he discovered otherwise. A relationship led him to the outdoors, to rock faces and rope systems. Then, in 2022, he joined the Canadian Para-climbing Team and travelled to his first international competition. It was the first time he had met other Canadian Para climbers. The experience rewired his understanding of what was possible.

“In 2022, when I first joined the team, there were five of us,” he recalls. “That was the first time I ever met any other Canadian Para climbers. Before that, I didn’t think there were any organizations making climbing accessible in this country. I was wrong. There were programs in Toronto, and since then, more have been popping up. But it’s still not enough.”

The barriers we don’t see

Para-climbing in Canada is an emerging sport, a movement still in its infancy. Just a year ago, Para-climbing competitions in the country were virtually nonexistent. Now, there is momentum.

The reason for this delay is not an absence of interest, but an absence of infrastructure. In countries like France and the United Kingdom, Para-climbing is well established, but in Canada, the infrastructure is still developing. The barriers, Misuraca explains, are rarely physical. They are logistical, financial, and cultural. Equipment is expensive. Travel is expensive. Training requires both.

Many climbing gyms do not have adaptive programs, and those that do often rely on volunteers willing to dedicate time to helping a climber learn the sport. Setting routes—selecting and securing holds to create climbing problems—is an expensive endeavour. It requires gym space, expert route-setters, and often, temporarily closing off sections of the facility. If a gym perceives that there aren’t enough Para athletes to justify the cost, it becomes a vicious cycle: without events, there are no climbers. Without climbers, there are no events.

“A lot of Para climbers don’t have extra funding,” he says. “They’re barely scraping by. They can’t afford to get themselves to and from a climbing gym, to pay for shoe and harness rentals, to cover gym entry fees. And then they need someone who is willing and able to belay them or even teach them how to climb.”

That is why competitions matter. Numbers matter. The United States faced a similar challenge. In 2015, when they hosted their first Para-climbing nationals, only 10 athletes competed. Fast forward to last year’s event: over 200 climbers participated. The question is no longer whether Canada has enough Para climbers. The question is how to find them and give them a place to compete.

For Misuraca, who is based in Ontario, the logistics of training alone present a daunting challenge. Take transportation. He is one of Canada’s top Para climbers, who is visually impaired, and cannot drive. To get to a gym, he must take a bus from Stratford to Kitchener, then rollerblade or run several kilometres to reach the gym itself. When winter arrives, his skates are swapped for running shoes, and his daily commute becomes a cross-training session in disguise. He trains largely on his own, finding partners when he can, adjusting to the inconsistencies of preparation.

But he is fortunate as some gyms, recognizing his talent and dedication, now allow him to train for free. But this is not the norm. The financial burden of Para sports remains significant. Specialized gear, and travel costs add up quickly. Misuraca competes at an international level. He represents Canada in Para climbing events. Yet unlike his competitors from other nations, he has no dedicated coach, no full-time support system.

Then, there is the matter of perception. He moves through the gym with ease, navigating the space faster than many able-bodied climbers. Unless he is using his headset, his disability is nearly invisible. It is only when others see him climbing with assistance that questions arise.

“You don’t look blind,” is a statement he hears often. At first, it frustrated him. But a friend offered a different perspective: when people struggle to reconcile his success with their own expectations, they make excuses. Instead of taking offense, he now frames it as an unintended compliment.

The economics of exclusion

Climbing gyms, like all businesses, operate on margins. Accessibility—whether it be ramps, adaptive equipment, or training for staff—costs money. Misuraca recalls a competition in Montreal where the organizers wanted to make the event fully accessible. The cost? $20,000. The response? A simple, “I can’t afford that.”

It is a rational answer. But it is also a revealing one.

For many Para athletes, the barriers to entry are not just social but structural. A wheelchair user might technically be able to enter a gym, but once inside, they may find themselves unable to reach the climbing mats. The solution is simple—lowered access points, ramps, a slight reconfiguration of space. But solutions cost money, and when the number of affected individuals is small, the financial incentive to change disappears.

While cost is a real factor, framing accessibility solely in terms of cost-benefit analysis or the number of people impacted limits creative thinking about access. Access is not just about physical modifications—it’s also a mindset. When we move beyond seeing accessibility as a financial trade-off and instead approach it as an opportunity to rethink and redesign spaces, we open the door to more inclusive solutions.

Misuraca lives with his parents to make ends meet, but even with the savings from not paying rent, he still has to self-fund his training. He is his own coach. And, when he travels for competitions, he stays with friends because hotels are too expensive.

Looking forward

There may be a lesson in how brands are starting to see value in adaptive sport. Companies like The North Face and National Geographic have funded high-profile Para climbers, Ben Mayforth and Maureen Beck, recognizing not just their athletic talent but their ability to expand the reach of the sport itself.

Also helping to raise the sport’s profile was the announcement of Para climbing being included in the 2028 Paralympic Games in Los Angeles. And in February 2025, Canada’s first-ever National Para climbing Championships were held in La Prairie, Quebec. Misuraca finished first in the B3 male category, which is for athletes with partial or residual vision and require a sighted guide, a caller, for navigating the climbing route.

If his past self could see him now, would he believe it? The man who, 6 years ago, thought he was worthless, now competing at the highest levels in 2 sports on national teams? Misuraca’s Instagram handle, @theblindexplorer, is more than a name—it is a philosophy. It suggests movement, curiosity, the relentless pursuit of new frontiers. The challenge is not just adapting to new ways and the challenges that come with it but dismantling societal ones. Misuraca’s story is proof that the boundaries of sport are often dictated not by the athletes themselves, but by the assumptions surrounding them.